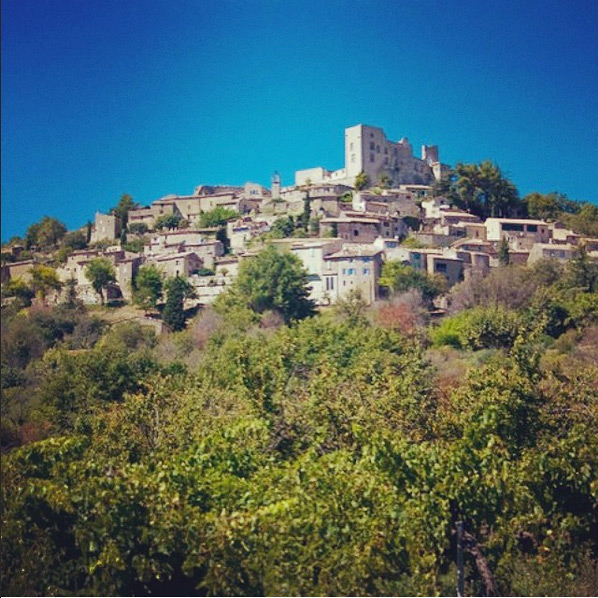

Deep in France's Luberon Valley, between the villages of Lacoste and Bonnieux, stands a 16th century farmhouse and several outbuildings known as Maison Basse.

"Maison Basse has always held an important place in our hearts," explained Jean Pierre Soalhat, a professional mosaicist, preservationist, and Lacoste historian. "From the perspective of the village, it's the focal point of the valley. From the perspective of time, it's a cultural touchstone and a memorial to our history. Now, this regional treasure has risen from ruin."

This is the story of the revitalization of Maison Basse, told by SCAD president and founder, Paula Wallace.

The Valley

| Date | Historical context of Maison Basse |

|---|---|

| Prehistory | France has a long history of pre-occupation, including our human ancestors — Homo Erectus and Cro-Magnon. There are many sites of Paleolithic occupation in the region, including Fort Pourquière. |

| 125 BC | The Romans establish Narbonensis (now the Provence-Languedoc) and three years later, Aquae Sextiae (Aix-en-Provence). |

| 58–51 BC | Julius Caesar conquers Gaul. |

| 3rd century BC | The Pon Julien is built by the Romans. |

| 3rd century | Roman Empire is in decline. |

| 476 | Collapse of the Roman Empire; Provence falls to the Visigoths. |

| 536 | Provence is ceded to the Franks. |

| 1056 | Lacoste first appears in written record, listed as Costa. |

| 1163 | Construction of Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris begins. |

| 12c | Construction of Maison Forte in the Lacoste upper village begins. |

| 1305–1378 | The Avignon papacy. |

| 1464 | The King of France establishes the postal system. |

| 1481 | Provence is given to the King Louis XI and becomes part of France. |

| 1532 | Lacoste embraces reformed Protestantism. |

| 1539 | French imposed as the official language of Provence. |

Maison Basse is located in France's Luberon Valley — a region that has been inhabited since Neolithic times.

It emerged as a cultural crossroads during the 2nd century BC when it was named the first Roman province outside of Italy. Roman Gaul, as the area was then called, experienced a period of unprecedented peace, prosperity, and technological advancements. One can see these vestiges of Roman innovation still today in the region's numerous aqueducts, forums, bridges, and roadways.

![]() La Via Domitia, the first paved road for trade and travel linking Italy and Hispania, passed directly through the Luberon Valley. It is a route so ancient, it is said to trace the mythic course of Hercules.

La Via Domitia, the first paved road for trade and travel linking Italy and Hispania, passed directly through the Luberon Valley. It is a route so ancient, it is said to trace the mythic course of Hercules.

An empire-wide decline in the 3rd century opened up the region to centuries of invasions and long-term occupations by the Visigoths, the Franks and, then, the Saracens. In 1056, the Holy Roman Empire was reestablished in the region, and it is around this time that we find the first written record of a hilltop village named Costa. Here, a towering château overlooking the valley was being built with stones from a nearby quarry.

Architectural histories of Provence's late Roman period typically tell the proliferation of grand religious structures in the Romanesque style: the Cathédrâle Saint-Saveur in Aix, the Abbaye de Senanque near Gordes, and the Cathédrâle Saint-Trophîme in Arles. Although less lauded, of equal importance are the utilitarian structures that pulsated with everyday lives of everyday people, and they played a vital role in community development.

Just as stones were positioned for constructions of grandeur in Aix and Arles and up north in Paris, the foundation was laid for a farmhouse below Lacoste. What remains of this structure, and what it has become over the course of 600 years, we call Maison Basse.

The Vernacular

| Date | Historical context of Maison Basse |

|---|---|

| 1562–1598 | Wars of Religion. |

| 1598 | King Henry IV declares the Edict of Nantes, declaring Protestantism legal. Religious massacre of Lacostois ensues and the village is burned. |

| 16c | The first section of Maison Basse is constructed atop a 13th century ruin. |

| 1608 | Founding of Quebec. |

| 1632 | Construction of the Taj Mahal begins in Agra, India. |

| 1643 | Louis XIV becomes king with Mazarin as his principal minister. |

| 1662 | Father Marquette and Louis Joliet discover the Mississippi River. |

| 1663 | The Temple (1610) in Lacoste is demolished by order of the King. |

| 1664 | Tartuffe is penned by French playwright Molière. |

| 1675 | Construction of Christopher Wren's St. Paul's Cathedral begins in London, England. |

| 1680 | Louis XIV visits Provence. |

| 1682 | The French Royal Court moves to Versailles. |

| 1685 | The edict of Nantes is revoked. |

| 18th century | Maison Basse serves as a carriage stop for the château of Marquis de Sade. |

| 1700 | Blackjack originates in French casinos, where it is called vingt-et-un, or twenty-one. |

| 1716 | Isabelle de Simiane sells Lacoste property to her cousin, Gaspard Francois de Sade, the grandfather of the Marquis de Sade. |

| 1756 | The beginning of the Seven Years' War. |

| 1768 | Marquis de Sade is exiled to Lacoste. |

| 1789 | The French Revolution begins. The Declaration of Human Civil Rights establishes freedom of religion in France. |

| 1792 | Lacoste is sacked by rioters; the château is looted and destroyed. |

| 1796 | In need of money, Marquis de Sade sells the château, and all of his land. |

| 1799 | The French Revolution ends. |

Maison Basse is an example of what architectural historians call vernacular architecture — a space that evolves over time to reflect its environmental, cultural, and historical contexts.

As SCAD historic preservationist Bob Dickensheets explained, "Every element of Maison Basse relates to the environment very directly, whether it's protection from the mistral or exposure to the sun."

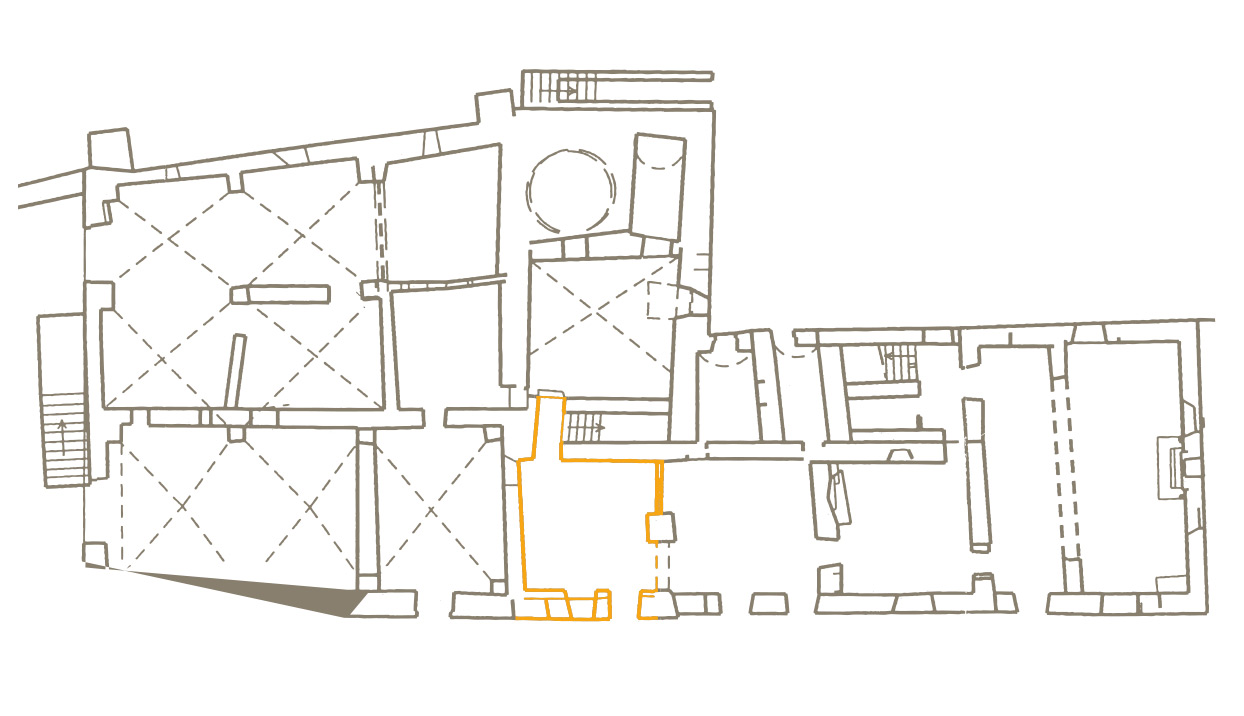

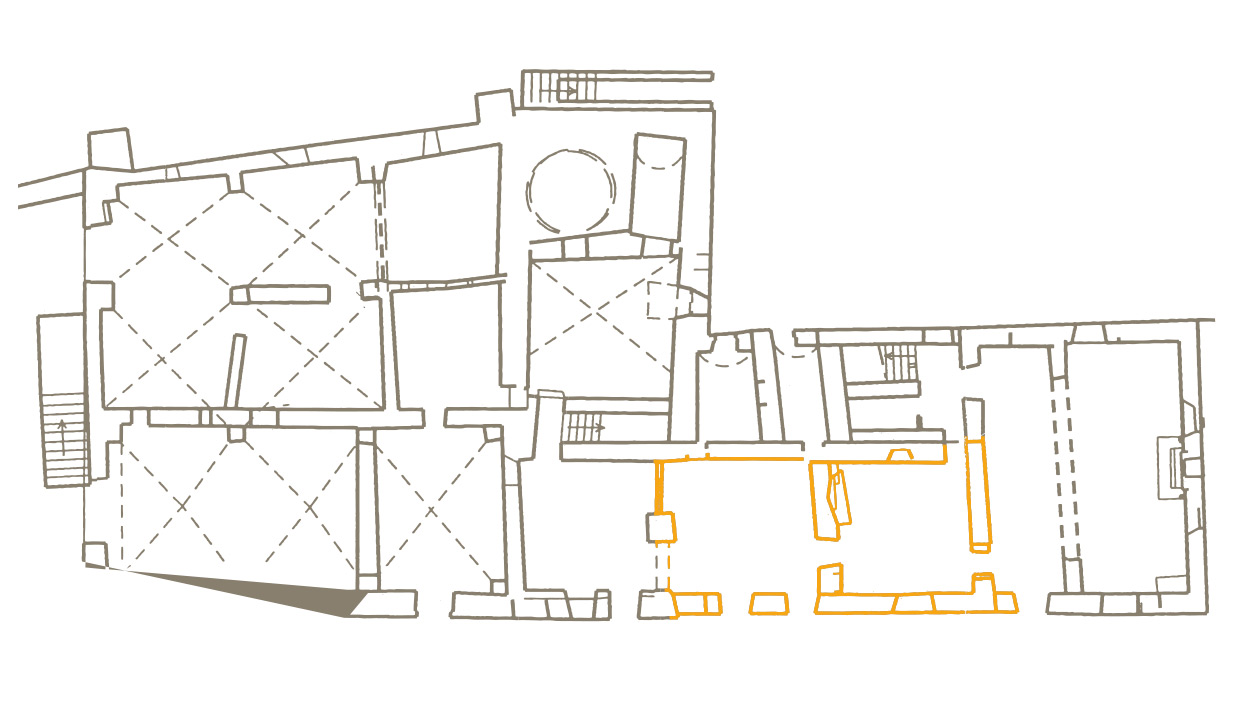

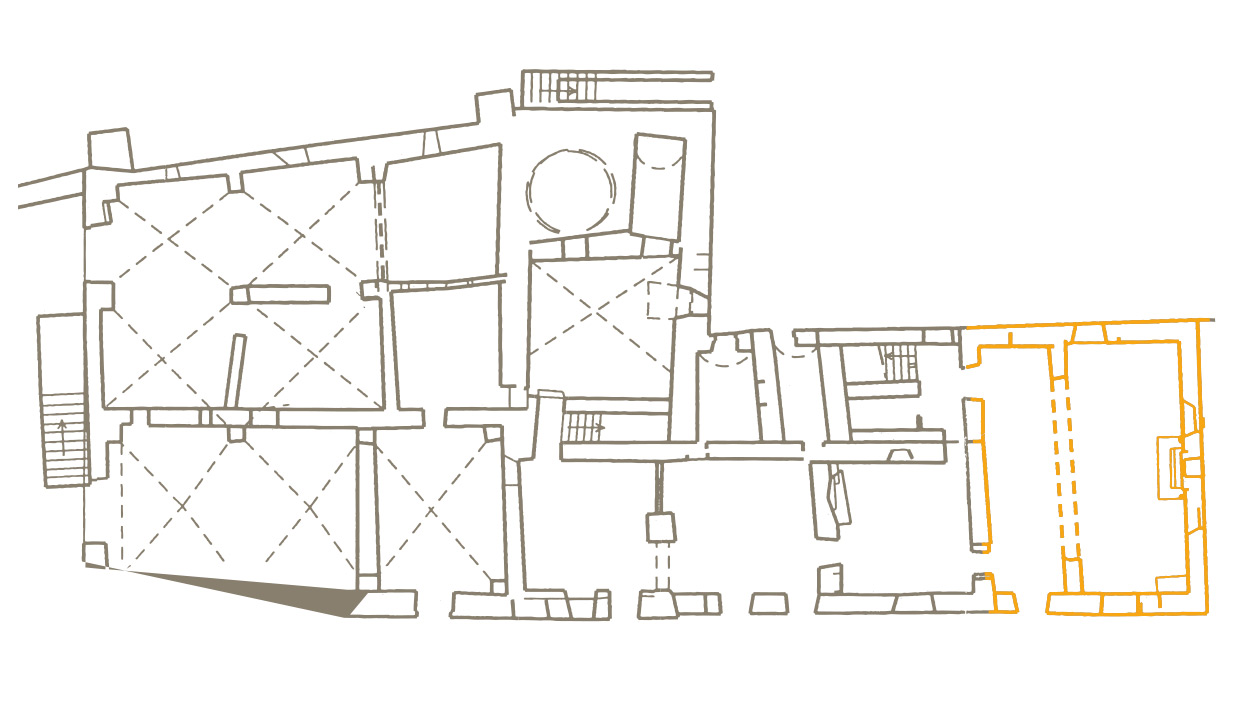

Over the course of four centuries, Maison Basse, like many other farmhouses in the region, expanded laterally from its original foundation to meet the needs of its inhabitants. During the 16th century, a one-room farmhouse was constructed on top of 13th century ruins. It was a utilitarian structure to accommodate the farmer, his family, and the livestock. Later that century, two living spaces were added to the east, while doorways were widened to allow wheelbarrows and carts to pass through the family living space.

The late 16th century was a tumultuous time in the region, as the entire area was embroiled in the Wars of Religion. Positioned in the valley directly between the Catholic village of Bonnieux and the Protestant village of Lacoste, the site of Maison Basse was neutral ground, a place where villagers could take out their grievances, and many did.

As SCAD alumna and preservationist Kate Firebaugh discovered, the site of Maison Basse was also a community hub. During initial excavations, for example, she and her team uncovered a massive community oven.

| Date | Historical context of Maison Basse |

|---|---|

| 19th century | Lacoste sees a brief time of agricultural and economic prosperity from the Roman Limestone quarries, but hits a slump in the second half of the century and a large potion of the upper village falls into disrepair and ruin. |

| 19th century | The lavoir is constructed at the Maison Basse. |

| 1804 | Napoleon declares himself the First Emperor of the French. |

| 1830s | Maison Basse comes into the possession of the Appy family. |

| 1837 | The Chamber of Deputies of France bans all games of chance and gambling. |

| 1889 | The Eiffel Tower is completed. |

| 1940 | The German Army enters Paris and the Vicy Regime holds control until the liberation of France in 1944. |

| 1945 | The parish of Lacoste is attached to Cavaillon. |

| 1950s | Bernard Pfriem visits Lacoste and Provence; Much of Lacoste is abandoned. |

| 1952 | André Bouer, a literature professor specializing in Marquis de Sade, buys the château in Lacoste and begins to restore it. |

| 1960s | A holiday camp is held for children at Maison Basse, but lasts a short time due to the absence of both electricity and plumbing. |

| 1970 | The Lacoste School of the Arts is founded by Bernard Pfriem. |

| 1970s | The last habitation of Maison Basse. |

| 1990 | Pierre Cardin purchases the ruins of the château and the nearby quarry. |

| 2001 | The Lacoste School of the Arts Board donates its Lacoste holdings to SCAD. The donation includes Maison Basse. |

In the early 18th century, an official connection to Lacoste's towering château on the hilltop was recorded through a bill of sale. As the document states, Isabelle Simiane, who owned the château at the time, sold the château and its land, which included Maison Basse, to Gaspard François de Sade. He was the grandfather of the infamous Marquis de Sade. In 1678, Marquis was exiled from Paris for his political and philosophical writings, which were deemed blasphemous by the church and state. He moved his family to the Lacoste château and proceeded to conduct a series of renovations to the property, including the addition of a private theater.

Around the same time, down in the valley, a grand salon was added to Maison Basse. The renovation transformed a simple farmhouse into a lively guesthouse for travellers and visitors to the château. Weary travelers, theater troupes, and servants often stopped at Maison Basse to play cards, enjoy a meal, or stay for the night in a small communal room. For a time, the space even served as an illicit gambling den. Guests would park their carriages at Maison Basse, grab a bite to eat, then climb Lacoste's steep and narrow streets on foot, horseback, or donkey.

In the late 18th century, riots associated with the French Revolution destroyed aristocratic properties throughout France, including the Lacoste château. Facing destitution, Marquis de Sade sold the château and all of its land, which included the Maison Basse site. Eventually, the site came into the hands of Michel Mathieu, a farmer in the region who divided it between his five children. In the 1830s, the site was acquired by Lacoste's Appy family.

Over many decades, the structure continued to change hands and expand laterally until there were 28 rooms. Before SCAD came along, the last occupation was a summer camp for young children that closed in the 1970s.

The Revitalization

The Upper Village

In 1999, Bob Dickensheets received a call in Savannah from some concerned Lacoste citizens.

A 13th century wall in a culturally significant farmhouse down in the valley was crumbling, he was told, and Lacostois sought advice on what to do. Bob, never too far from adventure, packed his bags, flew to France, and spent the summer working to stabilize the wall.

Over the next couple of years, Bob and I made several trips to Lacoste. There was an established arts study program at the Lacoste School of the Arts, and a handful of SCAD alumni attended. Then, in 2001, when the Lacoste School of the Arts was searching for an educational institution to shepherd the school into the new millennium, their board gifted 30 buildings in the village — dating from the 9th to 19th centuries! — to SCAD. Maison Basse was included in this donation. This exchange was possible primarily through the gracious work of SCAD board member Nancy Herstand and Jacques Tézé. Nancy and Jacques played an integral role in introducing the two non-profit institutions and their dedication to the process made the transition seamless.

The properties in the upper village were not exactly turn-key: modern plumbing and electricity were rare, stairs were falling in, windows falling out, and roofs leaking. Bringing these spaces up to SCAD living and working standards was truly a community and collaborative effort. SCAD preservationists, alumni, and staff all worked alongside local masons and specialists to make the spaces suitable for SCAD students beyond the restoration process — selecting furniture for each room, hanging specific art, hauling books to fill the SCAD Lacoste library, transforming medieval caves into artist studios, and photography darkrooms.

In the fall of 2002, with walls barely dry, we welcomed 32 students from all over the world to SCAD's new study abroad location in France.

First Impressions

While the properties in the upper village were modernized relatively quickly by a team of SCAD designers and preservationists, Maison Basse posed more serious challenges.

It was pretty far off our radar during those first few years. To put it bluntly, it was a hazard zone — dangerous to even walk through. We'd take pictures, make drawings, and even sometimes ask ourselves: is this worth it?

When you looked down upon Maison Basse from the upper village, you saw a pile of stones and a gaping hole in the roof. But inside the space, stepping into worn areas on the stairs where centuries of people had climbed, seeing, up close, the hand-crafted details from 600 years of expansions and alterations, there was no denying that this project was both necessary and important. And when a grant arrived in 2004 from the Bill Hillman Foundation, the project was finally able to commence.

Each room at Maison Basse presented its own unique set of challenges. Most noticeably from the vantage point of the upper village, the roof of the main building — once a hayloft — had completely caved in. In another room, so many doors and windows had been added over time that there was, essentially, no exterior wall. Another room had no foundation; instead, it was built directly on top of dirt. And in another area, a tree had pushed straight through the roof. Thick ivy vines drove the interior stairwell away from the building and into the road roughly two feet away.

Digging out rooms, unpacking stones, and scraping plaster from the walls, the SCAD team found that some stones were in stark contrast to others — some in a 17th century style, others shaped in a 12th century style.

SCAD eventually discovered that Maison Basse reflects the regional practice of incorporating pre-existing structures and materials, whether rough stones from nearby fields or finely carved stones from a house in the upper village. For example, off of the wall that was part of the original 16th century space, there was a small and anomalous (especially for a farmhouse) ornate balcony element. This piece most likely came from an abandoned home of a very privileged family in the upper village, and was reused here during one of the many additions. At one point in time, before the room was enclosed, the balcony would have offered an exquisite view of the château. If you were able to look upon the château, that meant you held a position of great social importance. So, whoever lived in Maison Basse during that time would have been related to the château's owner or had the rare permission to look directly upon it.

Creative Solutions

The main challenge with Maison Basse was finding a solution that simultaneously respected the space's historic significance and made it functional for contemporary and future needs. As with all SCAD preservation projects from Savannah to Hong Kong, we like to work within the existing confines of a historic space — it presents challenges, calls for restraint, and requires the most creative solutions.

The main challenge with Maison Basse was finding a solution that simultaneously respected the space's historic significance and made it functional for contemporary and future needs. As with all SCAD preservation projects from Savannah to Hong Kong, we like to work within the existing confines of a historic space — it presents challenges, calls for focus, and requires the most creative solutions.

I remember walking through Maison Basse with the SCAD design team in 2004, talking through each room's new function. After a couple of years' worth of work, there were still caves of rocks, unstable walls, and debris throughout. We entered on the barn-side of the building — where the manger once was. I gazed at the stone trough, which had these curved indentions marking where horses placed their necks to sip water for hundreds and hundreds of years. The space was earmarked to become a conference room, but looking around, in the middle of dusty ruins, I saw an intimate dining nook for faculty, students, and visiting artists. We hadn't even planned for a cafeteria, but I've always believed that some spaces just know what they need to be … and you have to trust what the walls tell you.

Over time, the spacious dome-styled 18th century community oven on the ground floor was transformed into a reading nook. On the top floor, in the former hayloft where the roof had caved in, we installed a massive skylight and created an expansive painting studio. Adjacent to the studio, we added a Mac lab. A staircase was added on the west side of the building, as was an ADA-compliant elevator. Modern plumbing, electricity, and wireless internet was introduced throughout. Outside, in the space between Maison Basse and the barn, we added a pool for recreation and a magnificently landscaped lawn, which serves as a breakout space for students and faculty.

In 2005, because of our work at revitalizing Maison Basse, I was appointed Chevalier dans l'Ordre des Palmes Académiques by the Conseiller Culturel and Consul Général of the French Embassy in the United States of America.

The Details

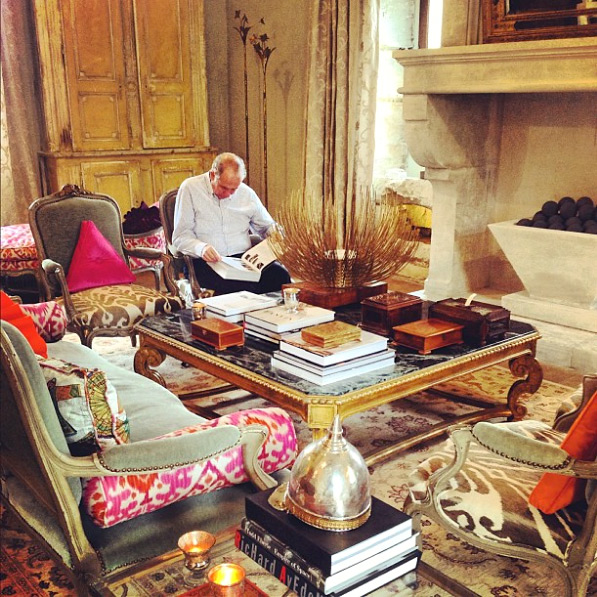

In the summer of 2012, with the majority of the preservation process complete, I spent several weeks in Savannah and Atlanta with SCAD's exhibition staff.

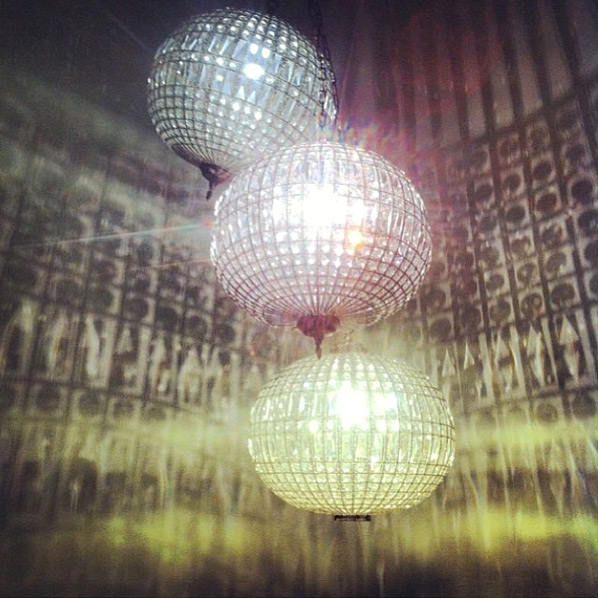

There, we combed through SCAD's permanent collection — SCAD student and alumni paintings, furniture, sculpture and light fixtures — choosing artworks to adorn and illuminate the walls and rooms of Maison Basse. I wanted an element of discovery and surprise at every corner; in every bedroom, a different SCAD artist is featured. The goal was for each space to inspire students and other guests to create artwork of their own.

Late that summer, my husband Glenn and I traveled to Lacoste to curate the final decorative details. We chose furniture, fabrics and unique décor from Provençal markets, including five-foot swans, which previously adorned a merry-go-round, to whimsically surround the perimeter of the pool. Bookshelves and tables were stacked with an enviable collection of art history and design books. Twin beds were covered with colorful quilts and vibrant down pillows stacked on sofas and chairs. Sculpture and lamps designed by SCAD students were thoughtfully placed. In a typical university residence hall, it is all about making sure that every space is the same. Here, though, every space is purposefully unique.

In a small corner enclave inside the reading room, for example, I created a battle scene with miniature soldiers and other toy figurines found at the antique market in Isle sur la Sorgue. The enclave was the location of the community oven's original stove, just large enough for one pot on a minimal fire. Beside this battle scene, I left a leather-bound journal and pen, and wrote the first few pages of a story inspired by the interacting characters. Much like the story of Maison Basse, which has been shaped by those who have passed through, my hope is that those who encounter this scene will be inspired to create its story as well.

The Reveal

"The Lacoste program has profoundly moved me to a place where I desire only to break out of any creative boundaries that were set before me. It has instilled in me an artistic thirst for new worlds of stylistic and conceptual development."

–Grant Whitsitt, animation major

With the revitalization of the Maison Basse main building now complete, nearly 300 students from all around the world who study at SCAD Lacoste each year have the incomparable opportunity to live and learn in this inspired space.

Courses of study taught in this enlightened environment, known for the purity and magic of its light, include painting, photography, art history, writing, fashion design, historic preservation, and more disciplines. Studying in this pastoral landscape is truly a once-in-a-lifetime learning and living experience.

Lacoste is a living laboratory for SCAD students both in environment and the top-of-field guests who have taught workshops and courses within our university. SCAD Lacoste's distinguished guests include illustrators Nina Weber and Alain le Quernec, fashion designers Shane Gabier and Chris Peters, photographer Jamie Beck, Oscar-winning writer Geoffrey Fletcher, fashion journalist Lynn Yaeger, interior designers Ilse Crawford, Primo Orpilla and Verda Alexander, and artist Ingrid Calame.

Maison Basse was a long time coming. Roughly, six hundred years. Yet, just as significant as the details of its provenance is SCAD's mission-driven goal to advance Maison Basse as the next chapter in our university's commitment to international learning opportunities.

Perhaps hero of the Enlightenment, Voltaire, said it best: "Our country is that spot to which our heart is bound." In this spirit, SCAD is truly a global citizen, invested whole-heartedly in every community in which SCAD students live and learn, in every inspired space created for their benefit, and in every place their tremendous talents take flight.

We still have work to do.

Join SCAD's commitment to cultural preservation and international learning opportunities.

Help make adifference